From Gavels to Guns: Concourt Delivers Judgment Under Armed Escort.

Judges and the Burden of Clarity: The Quandary of Controversial Verdicts.

MPHO LUCAS BUTHELEZI Reports from Lusaka..

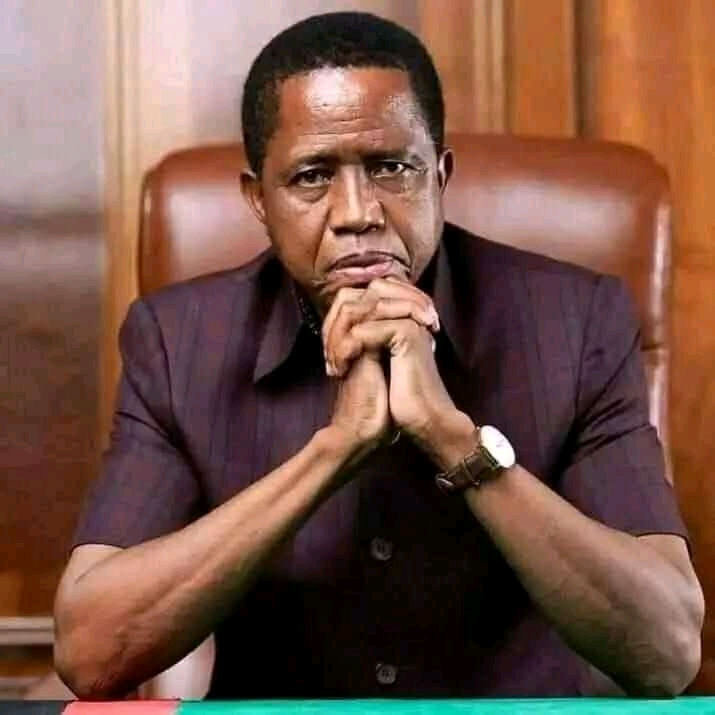

In the annals of Zambia’s judicial history, few decisions have left the populace as bewildered as the recent judgment on former President Edgar Chagwa Lungu’s eligibility to contest elections.

The court ruled that Lungu was eligible to stand in 2021 but simultaneously declared him ineligible for any future elections. This apparent paradox has sparked widespread confusion in a nation where clarity from the judiciary is often seen as the last refuge of order amidst political uncertainty.

One might ask, as many Zambians have, what the implications would have been if Lungu had triumphed in 2021. Christopher Chembe, a resident of the Copperbelt, succinctly voiced the collective disbelief: “If he was eligible to stand and had won, would his term not have created the same constitutional ambiguities the court sought to avoid? How can someone be eligible once but barred forever?”

Such questions hang heavily over a nation that has seen this matter litigated thrice, each time yielding outcomes that seem to raise more doubts than resolve them.

Legal scholars like John Rawls have long posited that justice must not only be done but also be seen to be done, a principle that underscores the necessity of verdicts fostering societal stability rather than exacerbating tensions. In his seminal work, A Theory of Justice, Rawls emphasizes that the rule of law thrives when judicial decisions uphold the principles of fairness, transparency, and predictability. Yet, Zambia finds itself grappling with a judgment that, instead of providing closure, appears to fan the flames of public skepticism.

The reaction in Lusaka, the capital city, speaks volumes. A heavy police presence around the Supreme Court precincts this morning suggested that the authorities anticipated unrest. Even after the verdict, police have continued patrolling compounds and most areas of the capital in heavily armored vehicles, a development widely interpreted as an attempt to intimidate citizens from reacting to the illogical judgment. This atmosphere of fear is a stark reminder of the power of judicial pronouncements to either calm or inflame a nation.

Alexis de Tocqueville, writing in Democracy in America, warned of the dangers posed by judges who fail to consider the broader societal implications of their decisions. “Judicial decisions are not merely for the moment but for posterity,” he argued, urging courts to ensure their rulings resonate with reason and justice rather than partisanship or expedience. It is a sentiment echoed by former South African Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng, who once said, “The judiciary must deliver judgments that edify, not confuse, a nation.”

In Zambia’s case, the judiciary’s role has been further complicated by perceptions of political interference. The firing of judges who previously handled Lungu’s eligibility case has cast a long shadow over the court’s independence. Such actions not only erode judicial credibility but also risk plunging the nation into deeper political divides.

As the dust settles on this latest judgment, Zambia’s judiciary faces a critical moment. Will it heed the wisdom of legal minds who stress the importance of clarity and impartiality? Or will it continue to render decisions that leave citizens more perplexed than informed? One thing remains clear: a nation’s faith in its institutions hinges on the judiciary’s ability to provide guidance that is as unassailable in its logic as it is in its legality. Without this, the armored vehicles patrolling the streets will become an enduring metaphor for a justice system failing its people.

Judges and the Burden of Clarity: The Quandary of Controversial Verdicts